- Rugby’s place-kickers need space to work at their craft, more than most: it hasn’t been in good supply during lockdown.

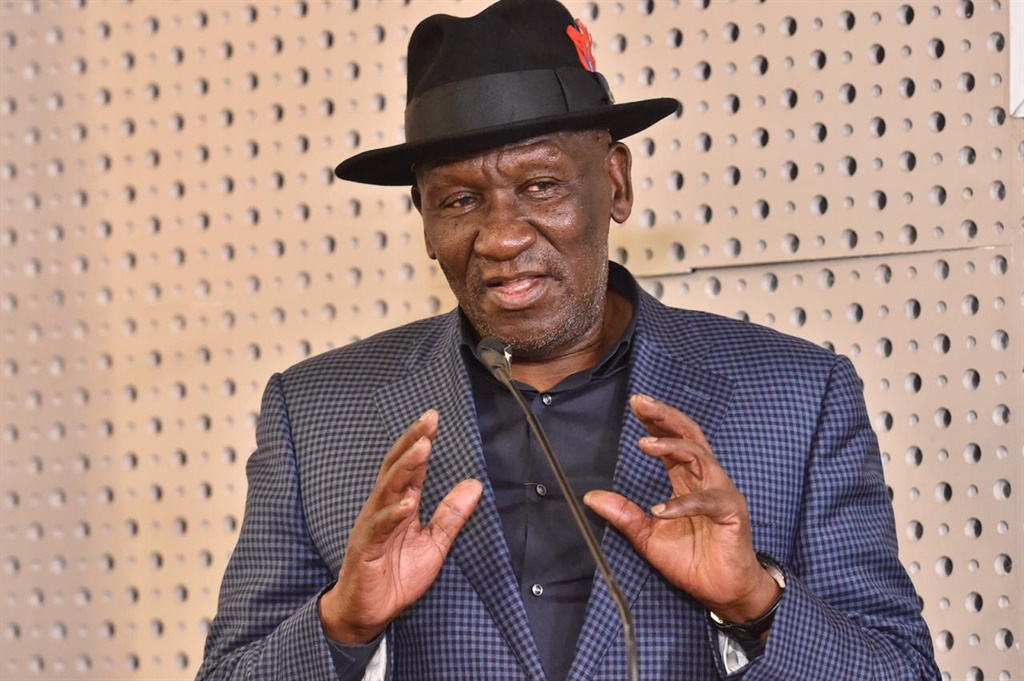

- Kick guru Vlok Cilliers warns that some will struggle to regain their premium levels quickly after an unusually long layoff.

- He says the likely spectator-less environment when play resumes will present other challenges for kickers.

Call it just another field of broken 2020 dreams, if you wish.

Our cautious rendezvous, marked by responsible social distancing and other trademark safeguards, took place on an unusually billiard-table-looking Markotter Field at Stellenbosch’s famous Paul Roos Gymnasium high school.

Normally by now – and despite the sparkling winter sunshine on the day – the first team’s lush, soft rugby field would be looking pretty churned-up after a solid term of regular use, and one still to go.

Instead it was in pristine shape, soaked in healthy morning dew … only giving a savage indication of how idle school sport has been due to the long-standing, enduring effects of the coronavirus pandemic.

“Ja … what a stuff-up,” sighs Vlok Cilliers, the dual former Springbok and SA Sevens player and now renowned, globetrotting specialist kicking consultant.

In that simple, yet succinct way, he was really just echoing the thoughts of millions – and more – who hold their sport, all sport, dear.

Stellenbosch is the kicking academy headquarters of the diminutive former Western Province flyhalf, recently nailed down for a further three years by the French national team to supervise that area of play in the lead-up to (and including) their home-staged RWC 2023.

All going well, and as Europe gradually emerges from lockdown, Cilliers will hook up with Les Bleus’ slow-building training cause in early August.

While still on home soil in the Western Cape, he has been listening to plentiful of parents’ agony over their matric rugby-playing (supposedly, of course) sons’ dispiriting inability, in what should be a key year in their rugby development, to impress scouts – including age-group ones from the professional franchises – for possible rookie contracts in the game.

Or, at the very least, to gain exposure to the (usually held) annual Craven Week, the prestigious U-18 edition, which had been intended for staging in Port Elizabeth round about now.

“Not everyone can afford to send their kids to university, either,” reminds Cilliers sharply.

He has a special interest in and affection for, of course, all players – and especially pivots – involved in the critical kicking aspects of rugby.

More specific than that, he has enormous sympathy for those who pride themselves in their work off a tee … a trade that was quite impossible to properly practice during the deepest weeks of lockdown for generally housebound players.

“Even a quite large suburban garden – if you are lucky enough to have that much – isn’t enough to be able to work on your place-kicking,” he says.

“You basically need a proper rugby field to do it properly.

“I have had people pleading with me to assist their boys (with their kicking) on a one-on-one basis, but it was just not possible during the severest part of the lockdown; the best I could provide was advice based on video footage and so on, or post up some recommended drills on Facebook.”

Whether for pro or amateur, younger or older player, an area known for the rare devotion and even obsessiveness of its practitioners has been especially savagely curtailed for weeks and months now.

Some creative kicking souls have tried their damnedest, as Cilliers reveals: “I could show you the video material I have received, of people erecting ball-catching nets in their gardens, or even placing mattresses upright in garages to act as receivers of a thumped ball.”

It is, of course, just not the same.

“Look, it’s one way of working, of making you feel you’re not giving up, and you don’t quite lose the feel of contact on the ball, or completely lose your rhythm and timing.

“But you can’t see where the ball is going; you get no proper indication of your degrees of accuracy, and distance.

“I know that in my own first-class career I would have been horribly frustrated by not being able to simply work at my kicking on a proper field … so I feel hugely for the current guys.”

Cilliers says all kickers, as with more general colleagues in the game, are used to the conventional lay-off during off-season annually.

“But this has been different: this hasn’t just been the usual three or four weeks or thereabouts of complete rest and inactivity.

“This has been months – and it is not over yet. When you start kicking from here, it will take you two or three weeks, I promise you, to get back properly in the groove … and that’s without even playing a proper game yet.

“When you start playing matches, that presents other renewal challenges and pressures.

“The other day a pro golfer, I forget who it was, said he found it so strange just striking the ball off the tee down the fairway; he felt a sense of nervousness … some kickers are probably going to feel the same.”

Cilliers says South African place-kickers are likely to also be required, at least initially, to have to do so in unfamiliar, spectator-free environments when competitive action eventually resumes.

“Sometimes as a kicker, you use the energy of the crowd to your advantage, whether it is your own fans’ enthusiasm or the more hostile feeling created by the rival audience.

“Now, you might land a brilliant kick, but you won’t get a crowd reaction of any kind … you just have to run back for the restart and keep having to create your own feel-good energy.

“But one thing we’re all learning this year, whether as players or onlookers: some rugby beats no rugby at all.

“It will be nice to just get to that point again.”

*Follow our chief writer on Twitter: @RobHouwing