- South Africa’s debt levels are breaking historical records.

- Director-General Dondo Mogajane said that debt levels risked breaching the 100% mark in 2023/24 if no changes were made.

- A zero-based budget will help government contain spending, but it has its drawbacks.

South Africa’s total debt is approaching R4 trillion, a first in its history, and Finance Minister Tito Mboweni is fast running out of options to turn the country’s fortunes around.

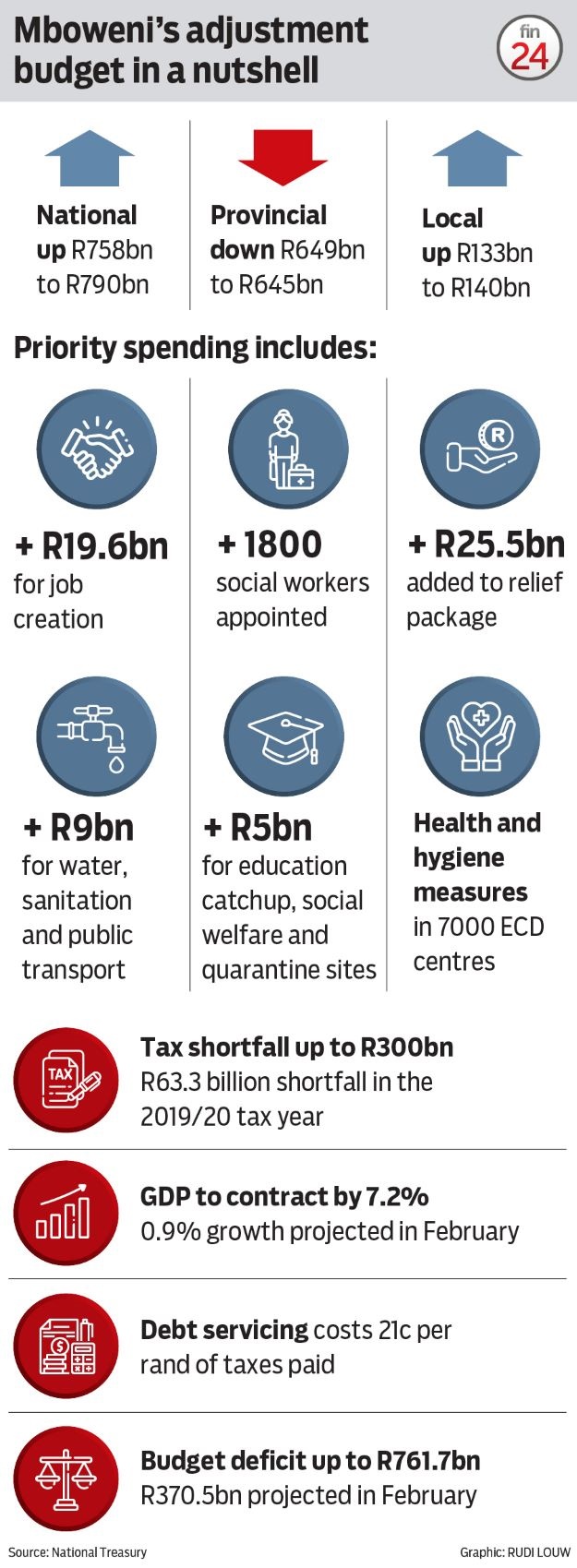

The supplementary budget tabled by the minister on Wednesday – which modifies the February budget to make provision for Covid-19 relief measures – indicated that SA is teetering on the edge of sovereign debt crisis, with little room to manoeuvre.

“A sovereign debt crisis is when a country can no longer pay back the interest or principal on its borrowings. We are still some way from that. But if we do not act now, we will shortly get there. The results are devastating,” Mboweni warned.

“We have been there before: in its closing days, the Apartheid government had to declare a debt standstill,” he added.

Cause for concern

Director-General Dondo Mogajane told journalists during a briefing after the tabling, that debt levels risked breaching the 100% mark in 2023/24 in a “passive” scenario if no changes were made.

A more “active” approach sees debt stabilising to around 87.4% in 2023/24, he said.

Analysts say the wolf is not yet at the door, though there is cause for concern.

“A sovereign debt crisis does not happen overnight, there are many signs that show you are headed toward a crisis. We have had many signs,” said economist and member of the president’s economic advisory, Thabi Leoka.

A sovereign debt crisis will become critical once investors start pulling out capital, or start demanding “buffers”. But SA is luckily not at that stage yet, as we are in a pandemic like the rest of the world, she added.

Elephant in the room

Treasury noted that the Covid-19 pandemic had exacerbated an already weak economic environment, revising its February projection of debt-to-GDP ratio of 65.6% to an unprecedented 81.8% or R4 trillion.

Stanlib chief economist Kevin Lings said that debt levels north of 80% of GDP would be something he had never seen in South Africa.

“That is the highest debt level SA faced at a government level,” he said. With debt becoming the fastest-growing area of government spending, resources would rapidly be diverted that should be available for government to deliver decent services. Lings added:

“Under those circumstances we are heading to debt crisis and potentially debt default.”

This has warranted the need for urgent structural reforms.

Leoka believes that government has been “dancing around the elephant in the room” in terms of tackling debt.

There are already sufficient funds in the system, which arguably haven’t been tapped into, she said. Some departments have not been working optimally, and government will have to cut spending from these departments – substantially more than it has already done.

When it comes to containing expenditure, Mboweni said in his speech that government will have to implement spending adjustments of R230 billion over the next two years.

Additionally, tax measures of R40 billion will have to be implemented over the next four years. Government had to revise the tax revenue target lower – this as SA will miss it February target by over R300 billion. Treasury recorded a R63.3 billion revenue shortfall in the previous tax year.

Gaping revenue shortfall

Liberty executive for channel support in customer and advisory experience Tendani Mantshimuli said the R300 billion revenue shortfall is serious and we have to borrow in order to fill critical gaps.

“This debt must be paid back. But what you don’t want to do is fail to pull together and find ourselves in a sovereign debt crisis … because the consequences are just too dire.”

– Tendani Mantshimuli

Deputy Finance Minister David Masondo echoed views that public debt was one of the bigger problems SA is challenged with, apart from unemployment. Part of the efforts in addressing debt will require evaluating whether some state-owned enterprises – which are increasingly becoming liabilities for the state – are growth enhancing or if they are “just a burden” on the fiscus, he said.

A zero-based budget

Mboweni believes that a zero-based budget will be instrumental in curtailing government spending, in that all expenditure items will have to be justified in terms of whether they are necessary. Mboweni said that growth-enhancing expenditure would be prioritised.

There are pros and cons to a zero-based budget, argued Momentum Investments economist Sanisha Packirisamy.

“They’re more costly and need more skills to carry it out. It will complicate the internal process from Treasury’s side. It’s more time consuming, more complex and it needs more people to be involved,” Packirisamy said.

It might be difficult for some departments to prove why they need funding, she added.

But it allows for an “active management” of expenditure items. It could even be more efficient, especially when it comes to funding projects that span across several departments. “The biggest positive is that we do see more transparency in a process like this,” said Packirisamy. “It leaves departments with a high sense of accountability.”

During a press briefing, Mboweni said that Treasury would be capable of coping with a zero-based budget system. “Is there capacity for it, yes there is,” he said. He added:

“With zero-based budgeting system we bring interaction between the technocrats and politicians in the process so that there is a conversation about what are priorities of political leadership, and what we would like to achieve in the short to medium term.”

Lings said that if government does indeed implement the zero-based budget it would signal that it is is able to make “the right type” of changes and that there is political will.

Efficient Group economist Dr Francois Stofberg said overall, while Mboweni made all of the right sounds in this emergency budget, there was still no real action in terms of partnering with the private sector, or tackling the fate of underperforming state-owned entities or cleaning up spending and governance.

“They were clever about where to get the money from in the budget. They reallocated spending. It only increases by R36 billion. They have had to borrow because the revenues are under pressure. There will be spending and activity, so revenue should recover,” Stofberg said.

“I think it is important to understand that this is a rescue budget and we cannot read too much into it or expect too much,” Stofberg added.