Steven Gordon, Human Sciences Research Council and Narnia Bohler-Muller, University of Fort Hare

Recent violent protests in Mahikeng in the North West province have prompted widespread commentary about what’s behind them, as well as their significance. Protests have raged in the province for two weeks and have seen at least one person killed and millions in property damage.

North West, which lies to the west of Johannesburg and borders Botswana, has also been affected by a two-month healthcare services strike.

Some have attributed the protests to demands for the delivery of basic services such as housing and sanitation, including concerns about the closure of health clinics. Others have focused on democracy and corruption related issues given that the protesters have been calling for the removal of the Premier of the province, Supra Mahumapelo.

All these factors have no doubt played a part in fuelling people’s anger. But the violent protests in Mahikeng and other parts of the province beg some serious questions about the functioning and state of South Africa’s democracy. Evidence from the latest round of a nationally representative South African Social Attitudes Survey conducted by the Human Sciences Research Council provides some profound insights into how people in that part of the country see the world. Each survey round consists of a sample of 3,500 adults older than 15 years. This opinion poll (which has been conducted every year since 2003) has enabled us to track public opinion in the North West.

The survey shows that over the past 15 years people in the area have been growing disgruntled with the political leadership in the North West province. Citizens are discontented with the status quo and want meaningful change.

The survey also shows that corruption has become one of the biggest concerns for residents of the province when it featured much lower down their list of concerns 15 years ago.

Another disturbing trend the survey highlights is that a significant minority of those polled view violent protest action as an effective way to achieve change.

A trend of growing unhappiness

The survey shows that public trust in local municipal government in North West has dropped dramatically since 1998 – from 56 percent under the then Premier Popo Molefe to 18 percent in 2017 under Mahumapelo. The steepest drop in confidence happened after the Marikana tragedy in 2012, when 44 people died. Thirty-four were shot by police during a protest at one of the mines belonging to platinum producer Lonmin.

Over the past 15 years people living in North West have also become more cynical about the way democracy, political leaders and the economy have performed in the country. Last year only 14 percent of North West residents said they were satisfied with the way democracy was working. This was down from 67 percent in 2005.

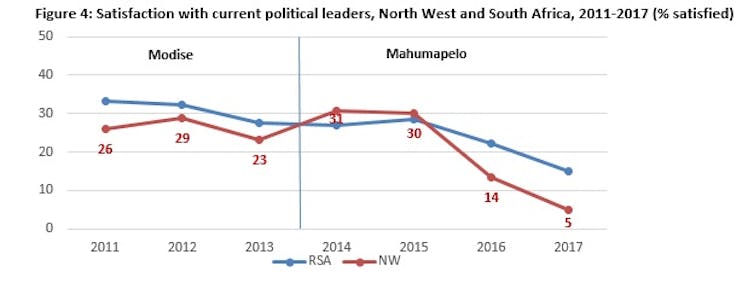

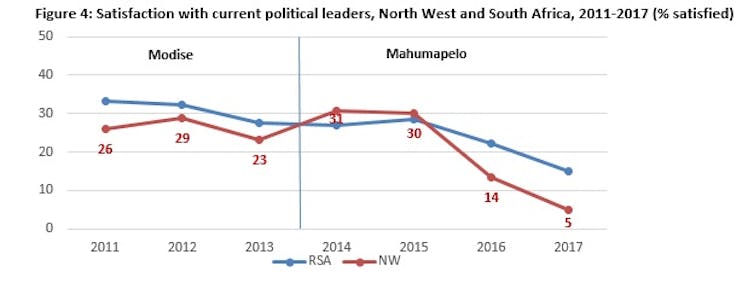

The vertical lines denote the period of office of the two most recent premiers of the North West province Thandi Modise, and Supra Maphumapelo. HSRC SASAS 2011-2017

The vertical lines denote the period of office of the two most recent premiers of the North West province Thandi Modise, and Supra Maphumapelo. HSRC SASAS 2011-2017

In addition, levels of public satisfaction with water and sanitation services have declined dramatically since the early 2000s. There has also been mounting and sustained discontent when it comes to the delivery of basic services such as electricity.

People’s political priorities have also changed dramatically over the past 15 years. When asked what national challenge was the most important to them, corruption was listed by only 5 percent of those surveyed in 2003. But by last year this has shot up to nearly a quarter with 23 percent listing corruption as their top concern.

Peaceful, disruptive, violent

A survey question posed to participants in 2016 sheds some disturbing light on how people view protests. Participants were asked about the acceptability and perceived effectiveness of three types of protest action: peaceful, disruptive and violent.

A third of North West residents had a positive view of peaceful protests. And only 19 percent said they thought peaceful demonstration would bring about positive change. An even smaller proportion (9 percent) thought that disruptive non-violent forms of action were useful.

A minority – 13 percent – said they believed that violent protests were an effective instrument for change.

This suggests that the violent protests in the province are largely being driven by a minority who see violence as a way to getting meaningful change. The implication is that the majority of inhabitants are unlikely to condone the violence and militant protests that occurred in Mahikeng.

Dire situation

The survey data shows a dire situation. It suggests that the Mahumapelo premiership has failed to address public concerns about service delivery and the local economy.

Nor do people in the province have any faith in peaceful protest as an effective way of securing change. It is, therefore, perhaps unsurprising that there has been a flare-up in violent protests.

The creeping disillusionment and loss of political effectiveness in the province is worrying. It is incumbent on the leadership of the governing ANC to ensure that discontent is heeded and that appropriate measures are taken to get the province running effectively again. In the light of this, it’s appropriate that President Cyril Ramaphosa is reported to have asked the premier to “step down”.

Jare Struwig, Benjamin Roberts and Yul Derek Davids were part of the research team that produced the survey on which this article is based.

The link to the survey in this article provides access to all the data. If readers require a more detailed analysis of the data, please contact the HSCR at datahelp@hsrc.ac.za.

Steven Gordon, Post-Doctoral Research Fellow, Human Sciences Research Council and Narnia Bohler-Muller, Executive Director Africa Institute of South Africa at the Human Sciences Research Council and Adjunct Professor of Law, University of Fort Hare

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.