President Cyril Ramaphosa gave weary and irritable South Africans something to look forward to when, on Sunday evening, he announced that the country will move to Level 3 of the lockdown on 1 June – but, as always, the devil is bound to lurk in the detail.

He has given six addresses to the nation since the state of national disaster was announced on 15 March, and where South Africans were broadly united in their support for the president and his government’s swift action more than two months ago, the national mood has become increasingly frayed as the lockdown began to bite.

Regulations announced by Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, the local government minister legally charged with administering the emergency directives, came under fire for the lack of logic and scientific evidence on which it was based, while the machismo of some ministers – notably Police Minister Bheki Cele – rightfully drew flak.

The legality and constitutionality of the National Coronavirus Command Council (NCCC), a newly established body attached to Cabinet but with no apparent statutory standing, has also been challenged as South Africans started to push back and demand answers.

Politics and ideology also came into play in recent weeks as questions were raised over the government’s continued banning of alcohol and tobacco sales, with Ramaphosa seemingly at first supporting the sale of cigarettes, only for Dlamini-Zuma to announce that the ban will remain in place.

And tension between some scientists on the Ministerial Advisory Committee (MAC) – a body of 51 eminent scientists advising the Minister of Health Zweli Mkhize – came to a head over the last seven days, with Professors Glenda Gray, Francois Venter and Shabir Mahdi, among others, criticising the government’s approach to scientific advice. They all broadly agree that advice from the MAC on issues, such as the regulations, aren’t listened to and that the scientists feel sidelined.

Ramaphosa on Sunday night sought to bring a measure of calmness to the fraught environment of recent times. Chief among those was that the economy will by and large be reopened, with retail, construction, manufacturing, financial services and almost every other sector set to return to business on Monday, 1 June.

But restaurants and bars, professional sport and the airline industry – as well as the tobacco industry – will remain closed or constrained in the levels of activity they can undertake.

The implications of the lowering of the risk level from 4 to 3 will be clarified in the coming days – but, as with previous announcements, the minutiae in the detail will determine to what extent South Africans will return to normalcy.

Alcohol sales will be permitted, as will exercise and more freedom of movement. We’re going to have to wait and see what exactly the amendments to the regulations say.

Ramaphosa explained the extent of the public health response and again, like in the past, reiterated the real fear that the full impact of the virus has yet to breach our defences. He said the lockdown has given the public health system time to prepare and authorities space to procure equipment and beds, and to construct field hospitals.

The president, clearly acutely aware of Mkhize’s strained relationship with key members of the MAC, reached out to them and thanked and acknowledged their contributions, saying their advice was sought before the address.

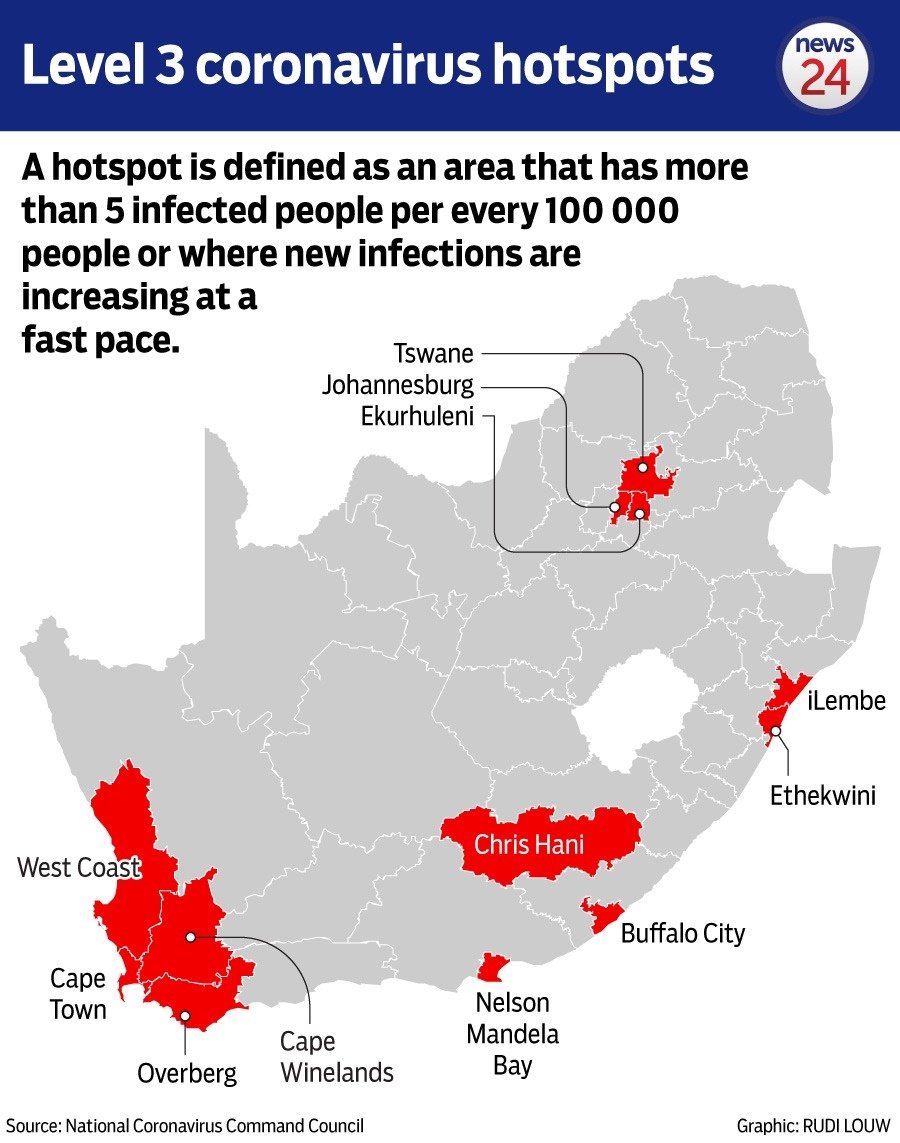

FULL TEXT | Ramaphosa unveils Covid-19 hotspots, dos and don’ts under level 3 lockdown

“We are extremely grateful for the work they have done and continue to do to ensure that our response is informed by the best scientific evidence. We appreciate the diverse and sometimes challenging views of the scientists and health professionals in our country, which stimulates public debate and enriches our response.”

It has been an almost impossibly difficult and complicated period to navigate – with much of it being the government’s making, it must be said. A broken public health system, a depleted national fiscus, a misfiring public service and a weak economy did not give Ramaphosa the armoury with which to tackle a global pandemic of uncertain scope and impact.

Before the pandemic hit, the country was facing its biggest socioeconomic crisis in decades, with unemployment soaring, economic activity declining and our investment grade tanking. The pandemic, and many of the responses to it, have conspired to only make matters worse.

Our ability to support and sustain livelihoods – either through job creation or social grants – has been severely damaged by the last 10 weeks. And the country’s biggest problems remain as they were two months ago: weak electricity generation, the state of public owned companies, the urgent need for economic reform and the reconstruction of state institutions like the NPA and SARS.

The lockdown could not be sustained, Ramaphosa said. And the spread of the coronavirus is going to get “much worse” before it gets better.

But, for now, a semblance of normality beckons. Even if we are a diminished country.