South Africa will likely not be able to prevent the exponential spread of Covid-19, with the full sweep of the disease to probably hit the country later this year.

And although South Africa acted much earlier than other nations in identifying the virus and implementing measures to halt its spread, it has only bought the country time to prepare for what scientists are calling “almost inevitable”: a dramatic rise in infections.

This is according to Professor Salim Abdool Karim, the chairperson of Health Minister Zweli Mkhize’s Covid-19 advisory group, who addressed a media briefing alongside other scientists on Monday night. It was the first briefing with the country’s top scientists since the coronavirus was first reported in South Africa on 5 March.

Karim was joined by among others Professor Glenda Gray, the chairperson of the Medical Research Council, Professor Koleka Mlisana, a microbiologist from the University of KwaZulu-Natal, and Professor Brian Williams, an epidemiologist formerly with the World Health Organisation.

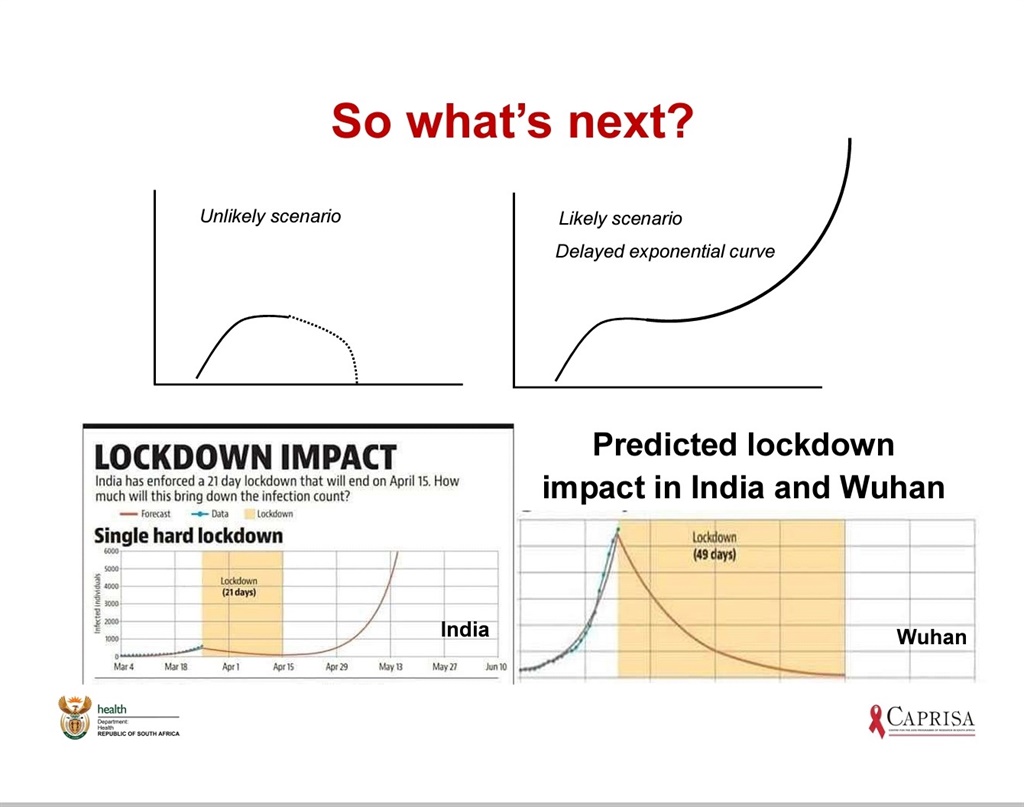

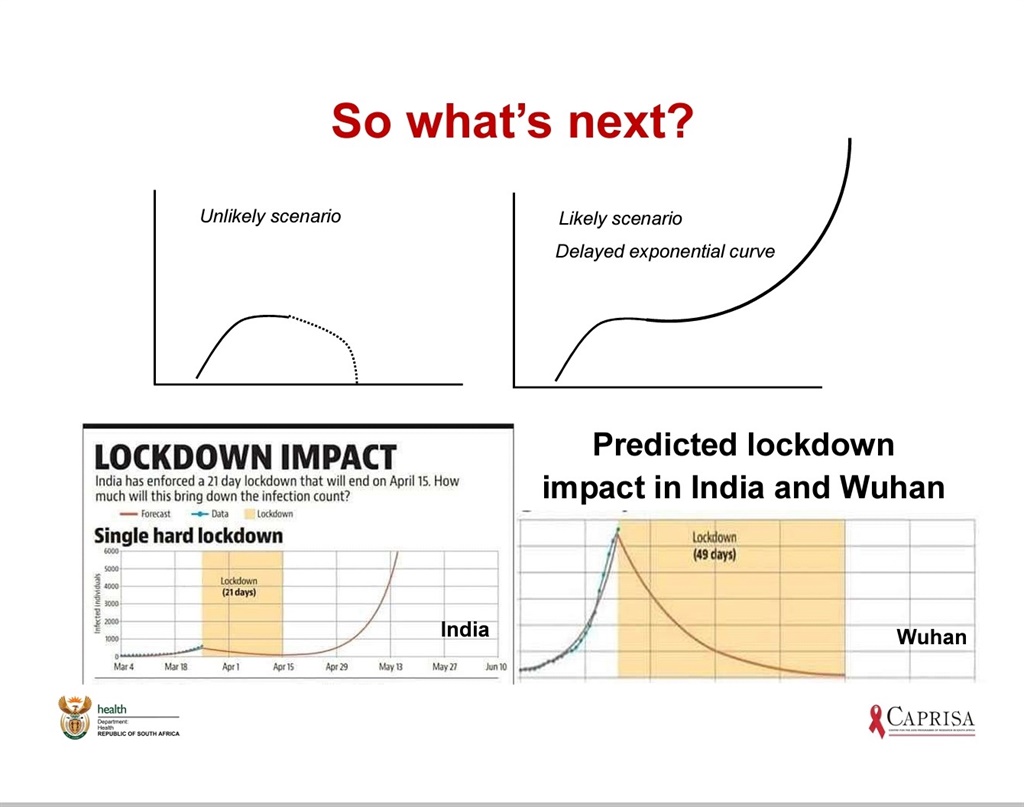

“What we have managed to do, is delay an exponential curve,” Karim said. “It is a difficult truth, but can we avoid the exponential spread? No… unless we have a mojo that other countries don’t have.”

He also explained:

- The lockdown could not be ended too abruptly, as we risk squandering gains made in the past few weeks and returning to an exponential rise in cases.

- A decision on a further lockdown extension would be informed by the rate of spread seen in average new daily cases between 10 and 16 April, which they were 95% sure would remain between 40 and 80 cases. Above 90 cases a day calculated over a week would result in a lockdown extension.

- Cases reported as confirmed today, were actually an infection that took place two weeks ago and infected persons are contagious days before they show symptoms.

- Plans were being developed for a systematic end to the lockdown, which would focus on not placing high-risk people in close contact with low-risk people.

- Testing criteria, restricted to people only with certain symptoms, has been widened in the past few weeks to pick up more cases, together with a significant increase in testing capacity.

- Major concern rested on Johannesburg, Cape Town and eThekwini (Durban), where a large outbreak was most likely to occur due to dense population numbers.

News24 reported on Sunday that government projections, presented to the Parliamentary health portfolio committee showed this peak infection scenario had been pushed back to September.

“No one in the world has encountered this virus. We have no immunity, no vaccine, no treatment. We are all at risk.

“As soon as the opportunity arises for this virus to spread, it will go back to the exponential curve,” Karim said.

A slide from Professor Karim’s presentation on Monday night, showing the most likely future scenario of Covid-19 cases in South Africa.

Importantly, lockdown and other initial measures had bought valuable time to prepare and attempt to contain hotspots.

Karim, a world-renowned figure in the field of HIV research and epidemiology, is the chairperson of a Ministerial Advisory Committee (MAC) made up of more than 20 professors, doctors and scientists who advise Mkhize and the National Command Council chaired by President Cyril Ramaphosa.

Karim was speaking at a media briefing on Monday night, scheduled to shed light on the technical aspects of government’s response.

Experts from the MAC and Mkhize explained what they expected in the coming weeks and months, and detailed measures taken so far and what had informed decision-making.

Karim and Mkhize steered clear of any projections on the numbers of people they expected to be infected at the peak of the virus, and how many people were expected to need hospitalisation or die from Covid-19.

Unique trajectory

Karim explained that while concern existed over whether testing was adequate in poorer communities and that many cases lay undetected in those areas, it was far more likely that early and decisive interventions had curbed the spread of Covid-19.

“We expected to see an exponential growth in our epidemic. But this didn’t happen,” he said.

Testing capacity had increased, and as such dispelled these concerns for the most part.

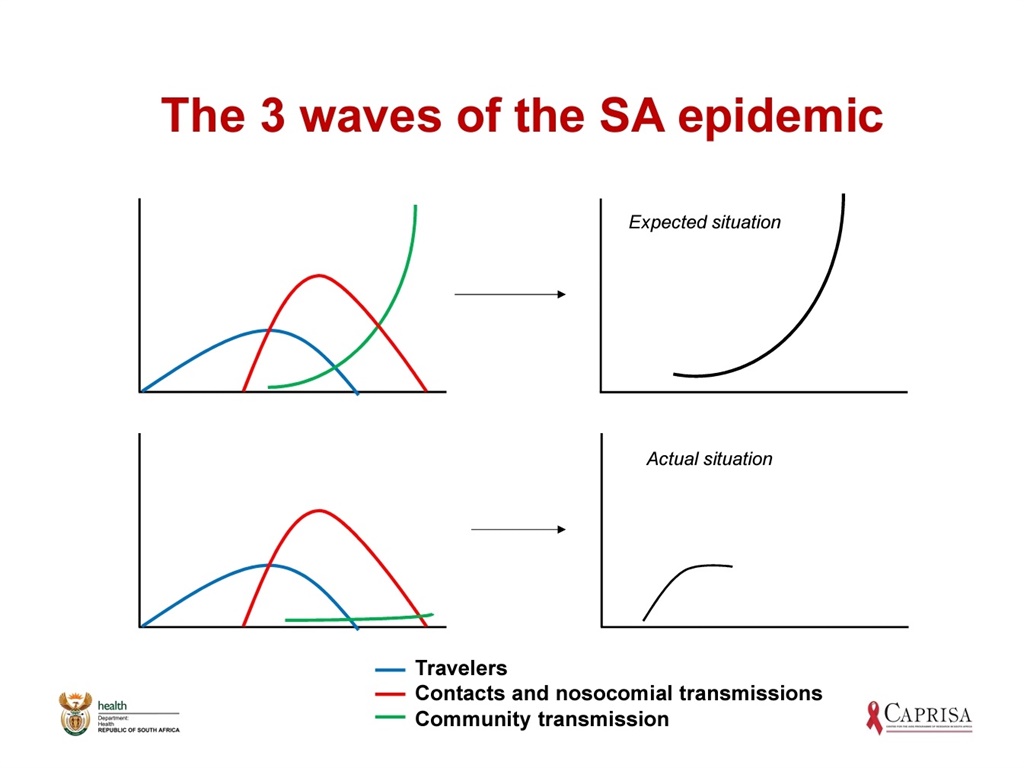

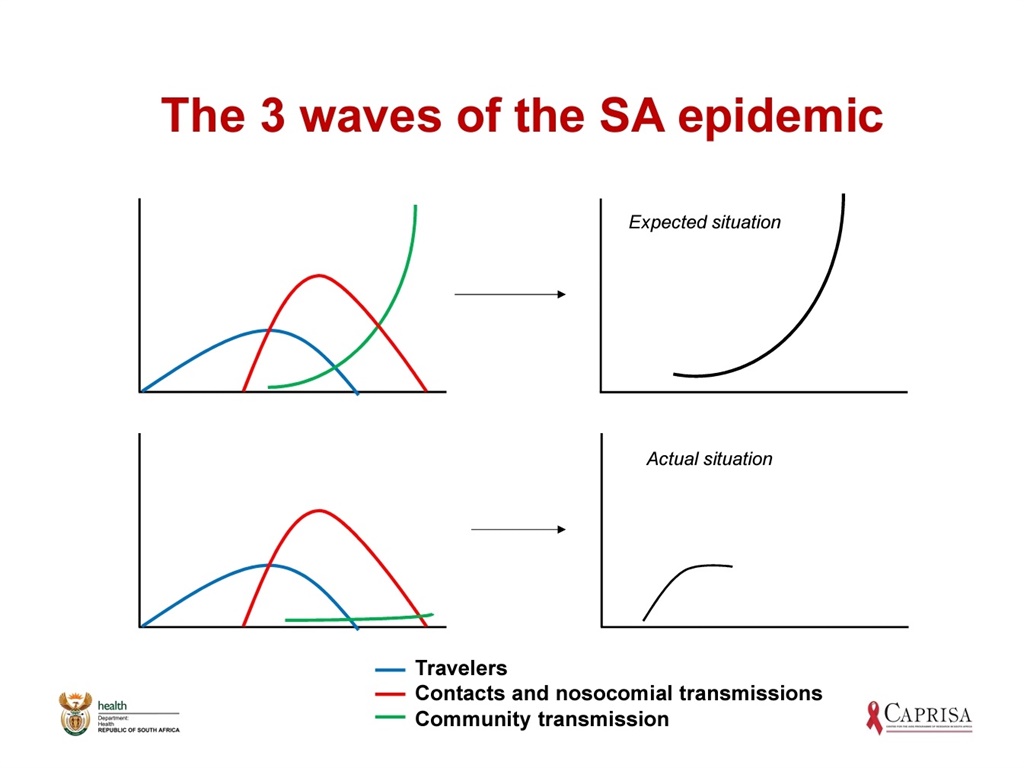

Professor Cheryl Cohen, the co-head of the National Institute for Communicable Diseases’ (NICD) Centre for Respiratory Diseases and Meningitis, explained that the country’s early cases were largely imported.

Imported cases refer to travelers who were infected abroad, who returned home and then passed the virus on to those they came into contact with.

Karim explained that these two groups – the travellers on the one side and the people they infected on the other side – were expected to pass the virus on to their communities.

A slide from Karim’s presentation on Monday night showing how the spread of the virus was expected to behave, compared with how it has behaved.

“When it [Covid-19] enters a community, it spreads like wildfire,” Karim said.

“For some reason, those two groups did not lead to this. We still have community transmissions, but it’s at a low level.”

As the local epidemic curve flattened and plateaued to a lower average number of daily new cases, testing capacity for the 80% of the population who do not have medical aid had been ramped up.

He highlighted that testing numbers were still too low.

Stages of response

According to Karim, government’s response was informed by eight key strategic responses planned and executed from early on.

The first four stages had unfolded in weeks past, while the next four stages would be informed by the data over the next two weeks.

- Stage 5, identifying hotspots to enable intervention quickly was key, and massive teams of health workers on the ground were essential to this.

- Stage 6 involved preparing the availability of medical care for the time when peak infection arrived, which had started some weeks ago. This included finding and building field hospitals where patients could be triaged before flooding hospitals. Karim said there was major concern over the readiness and availability of the healthcare system to deal with the number of patients who would require care.

- Stage 7, which Karim said he understood people did not want to speak about, was ensuring burial capacities could meet demand and preparing citizens for the psychological and social impact of large numbers of casualties.

- Stage 8 entails ongoing vigilance and surveillance, including testing campaigns at mines, schools and large companies to ensure a second wave epidemic did not occur after the initial outbreak is contained.

A slide from Karim’s presentation on Monday night shows how the infection curve, which closely tracked that of the United Kingdom, has changed significantly in the past weeks.

Stay up to date and stay healthy. Subscribe to Health24’s Daily Dose newsletter for important updates on the spread of the coronavirus. Register and manage your newsletters in the new News24 app by clicking on the Profile tab.